The Sparrow Problem

We’ve all read stories about and been enthralled by the idea of App Store millionaires. As the story goes… individual app developers are making money hand over fist in the App Store! And if you can just come up with a great app idea, you’ll be a millionaire in no time!

That may seem a bit hyperbolic, but that is honestly the way the public perceives success in the App Store. I can’t tell you how many people have called, messaged, emailed, and even cornered me at parties with an idea for “the next million dollar app”. For the most part, they try to temper their excitement, but it’s clear that the perception is that if I like the idea and help them build it, we’ll both be millionaires.

This mentality might seem a bit naive to those of us in the tech industry, but I’ll admit — as embarrassing as it is — that even with all my experience in the App Store, I still hope to someday have a runaway hit app that makes a million dollars and relieves some of the financial stress of hacking it out day by day as an indie developer in the App Store.

After 4 years in the racket, this is my best advice for making millions in the App Store: build a game, a gimmick, or an app that has some sort of revenue outside a one-time purchase. Oh, and if it’s a game, make it “free-to-play”. You might be able to build a sustainable business selling useful apps, and carve out a decent living for yourself, but it’s almost impossible to make millions.

Unless Google buys your company.

Sparrow did everything right. They built an incredible email app with broad appeal and released it into the hottest software market the world has ever seen. And yet it was a financial flop.

Flop? Yes. There have been whispers and conjecture to that effect over the past few days, but no one has been able to prove it. I can. I happen to have launched a $2.99 utility in the App Store last month and have a pretty good frame of reference for estimating Sparrow’s App Store revenue.

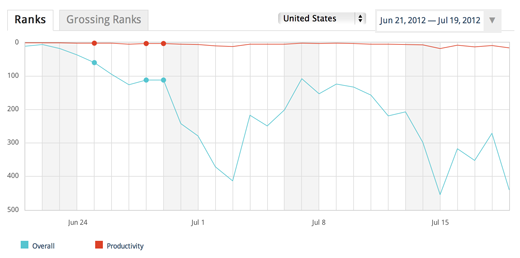

This is what Sparrow’s first month in the App Store looked like:

Chart generated at appannie.com

Chart generated at appannie.com

And Launch Center Pro:

Chart generated at appannie.com

Chart generated at appannie.com

I’m not ready to post exact revenue numbers, but I will say that Launch Center Pro’s first week in the App Store generated enough revenue to reimburse Justin (my partner in the app) and I for the ~300 hours we each spent building the app. We were completely floored by the success. To survive as an indie developer all you really need to do is break even on your time, and we had done that in a single week!

But as Launch Center Pro drifted out of the top 100, then out of the top 200, we started wondering where the bottom might be. We’d love to both work full-time on the app, and power through the huge list of awesome features we didn’t get to in 1.0, but it seems clear that working full-time on the app just won‘t be financially viable.

From our experience, a $2.99 app in the App Store needs to hover around #250 in the top paid list to sustain two people working full-time on the app. Launch Center Pro has already dropped below that threshold, and may keep dropping. The app may spike into the top 100 again as we release updates and build excitement about new features, but it’s hard to guarantee that will happen. In the past month as Launch Center Pro has been making enough to support us full-time, we’ve been working on it full-time. But as it dips, we’ve decided to scale our time proportionally. If it spikes again, that will give us the opportunity to either take a profit, or just scale our time back up and keep the app at or near break-even.

And that’s the Sparrow problem, break-even was not sustainable. They had to find a way to turn a profit — lots of profit — to provide their investors a decent return.

I haven’t been able to find any data on how long it took to build the first beta, which launched in October of 2010, but one of the co-founders, Hoa Dinh Viet, had been working on an open source email engine in his spare time for the better part of a decade. Even with the benefit of that experience and existing code base, I bet it took at least 3 months to get to beta, but it likely took several more months. And at some point during that time, designer Jean-Marc Denis joined Hoa Dinh Viet and Dominique Leca to make it a 3 person team — all working full-time on the app.

So, by the time Sparrow launched in the Mac App Store in February of 2011, they had been working on it at least 6 months, but likely longer. Thus, when Dominique revealed to Ellis Hamburger in August 2011 that Sparrow had made at least $350k in it’s first 6 months in the Mac App Store, they had already been working at least a year on the app. $350k is good money for a 3 person team working a year or so on a project, but I bet a significant percentage of that $350k was made in the first month, and that the sustained sales were no where near break-even for a 3 person team.

And Sparrow didn’t stay a 3 person team for long. In July 2011 Jean-Baptiste Bégué joined the team to work on the iPhone app. Then Louis Romero joined the team in January 2012. Bootstrapping to this size with revenue from Mac App Store may have worked if the team was living the ramen lifestyle, or digging into savings, but that’s tough to justify when talented contractors can easily make six figures, and full-time salaries for top engineers continue to be driven up by fierce competition. I don’t think the iPhone app would have been released as soon, nor the iPad app been as far in development as it was had Sparrow not taken a seed round in early 2011.

But taking that money was a blessing and a curse. It enabled the company to accelerate the pace of development, but completely changed the yardstick by which financial success would be measured. Sustainability was no longer the ability to provide a decent living for 5 talented people, they also had to provide a return to their investors. And by that new measure Sparrow was still a flop, even after the much anticipated release of their iPhone app.

Below is a chart of Sparrow’s ranking in the App Store since the iPhone app was released in March. I superimposed a dotted line at 250 to show the threshold Justin and I found necessary to sustain 2 people full-time:

Chart generated at appannie.com

Chart generated at appannie.com

By my estimate, the iOS app made somewhere around $400k in that 4 month timespan. Which is pretty incredible, but much of that was made in the first couple weeks while the app was still in the top 200. In the 60 days between April 8th and June 7th, I’d estimate they made less than $30k, a run rate of just $180k a year. The release of 1.3 and subsequent price drop in mid June generated another surge in the charts, but look how quickly that trailed off.

I don’t currently have an app in the Mac App Store, so it’s hard for me to estimate sales, but I’d bet the Mac version isn’t generating much more revenue, even at the higher $9.99 price point. The revenue spikes can help provide runway, but sustained revenue in the neighborhood of $30k a month doesn’t bode well for a funded company with a full-time team of 5.

With an iPad version deep in development, and a Windows app supposedly in the works, I’m sure the Sparrow team felt that the prospects were still bright. But as bright as those prospects may have been, I bet the first few months in the App Store were quite a reality check.

The thing is, the entire software industry is changing. Computer users used to spend hundreds of dollars for great software and pay again every couple years for upgrades. But over the past couple decades people have grown accustomed to getting more and more value from software while paying less and less for it. The web has played a huge part in that, but the trend was accelerated by the App Store and Apple’s management of it.

Back in 2009 I wrote:

The downward spiral in app prices caused by the Top 100 list and Apple’s relatively hands off approach during the first year of the App Store has created completely unrealistic pricing expectations that may haunt the entire mobile software industry for years to come.

In hindsight, I think “haunt” was the wrong word to use. Though it wouldn’t fit quite as well semantically, or be quite as provocative, I think the right word to use there is “change”.

Given the incredible progress and innovation we’ve seen in mobile apps over the past few years, I’m not sure we’re any worse off at a macro-economic level, but things have definitely changed and Sparrow is the proverbial canary in the coal mine. The age of selling software to users at a fixed, one-time price is coming to an end. It’s just not sustainable at the absurdly low prices users have come to expect. Sure, independent developers may scrap it out one app at a time, and some may even do quite well and be the exception to the rule, but I don’t think Sparrow would have sold-out if the team — and their investors — believed they could build a substantially profitable company on their own. The gold rush is well and truly over.

July 23, 2012

July 23, 2012